- Home

- Bobbi Phelps

Sky Ranch Page 2

Sky Ranch Read online

Page 2

Across from the ranch headquarters, a few single-family dwellings crowded together. These were the homes for several workmen and their families. Mowed lawns bordered the dirt road, and sagging clotheslines, laden with scrubbed garments, billowed in the breeze. From there Mike drove around various fields, explaining crops and irrigation systems to me. He stopped at a field, knelt in the earth, and sifted the soft soil between his fingers. I leaned on the truck’s door and looked out the open window, watching him grope the brown dirt.

“What’re you doing?” I asked.

“Just checking for clay and silt content,” he answered. “The land of Southern Idaho is made of sandy soil. That allows water to wet our crops and yet drains good enough for air to circulate. That’s why Idaho has such great potatoes.”

As we maneuvered another mile down the dirt road, he pointed to a platform with several silver cylinders sticking up into the air. The center pipe took water from a deep well while the other cylinders leaned inward to steady the main structure. We drove from the road to the center, bouncing over deep ruts made by wheels connected to structural arms of the rotating center pivot.

“Come look at this,” Mike said as he stepped from his pickup. I opened the door and followed him to the sturdy machinery. One arm protruded from the main water source. It sprayed water from various trusses moving on rubber wheels, circling through the newly planted field. I sat on the wooden platform, my elbows on my knees, and looked at Mike. He continued reciting facts about the different irrigating systems.

“Some wells drop about two thousand feet,” he said. “But we only have to raise the water five or six hundred feet.”

“Wow! I can’t believe how deep it is,” I exclaimed.

“This part of Idaho is basically a semi-arid desert. But we have a large aquafer below us. Using a well is much more efficient than irrigating with open ditches or siphon tubes,” he said.

“What’s a siphon tube?”

“It’s an ‘S’ shaped tube,” he said. “You stick the tube in a canal, holding the top end shut, and then drop it quickly into a crop’s row. When a farmhand gets the hang of it, he can move water practically as fast as he can walk. I’ll show you how it works on our way home.”

“How many center pivots do you have?”

“Right now, we have twenty-two. We’ve been changing our fields as fast as we can afford it,” he said. As he reached into his breast pocket and pulled out a cigarette package, shaking one loose and putting it between his teeth, he added, “Each pivot covers over a hundred acres.”

Just then, the pivot’s irrigating machine kicked on. A loud blast jolted the air and the platform began to shake. I must have thought I was going to plunge into the deep well. My legs rotated and raced as if I were on a bicycle. But I didn’t budge. I couldn’t get my butt off the platform. Mike came over and pulled me up, laughing so hard he spit out his cigarette.

“Where do you think you’re going?” he said, hooting with laughter.

“That’s not funny,” I countered. “I thought I was going to die!”

“No, you’re safe. Let’s head to the gravel pit next,” he said, snickering under his breath.

He ushered me back to the truck, and we traveled toward the middle of the ranch, turned north, and entered the gravel pit. Mike drove down a natural ramp formed of crushed rocks, leading into a large area filled with stones of all sizes.

“This is where we get gravel to shore up our roads. Whether it’s for plowing or leveling roads, we take care of ourselves. No government agency working here.”

Mike walked around the pickup and opened my door, holding out his hand to help me out. We strolled deep into the pit, surrounded by large boulders, and looked at the blue sky. He pulled me toward him, enveloping me with a kiss, as I wrapped my arms around his neck. It felt wonderful, like sunshine on water. After a few minutes, Mike pulled my hands from his neck and steered me back to the pickup. He opened the door and I glided over the vinyl seat. He slid in beside me. We were like teenagers . . . all moans, kisses, and body contact.

On our way back to the coffee shop in Murtaugh, he asked, “So, how’d you like Sky Ranch?”

“The ranch was fine, but the rancher was even better,” I said as I snuggled closer. “I can’t wait to see you again. Why not come for dinner? How does Friday sound?”

“Okay. I’ll be there after work, about six.”

I left him at the coffee shop and drove home, singing to myself along the way, “Six foot two, eyes of blue, but oh what those six feet could do. Has anybody seen my guy?”

* * *

By the time Friday rolled around, I had decided to prepare one of my favorite meals: spaghetti with homemade sauce. I had rented a two-bedroom farmhouse a few miles east of Hansen, about ten miles from Twin Falls. Mike would soon arrive for dinner and I wanted to impress him. After opening a bottle of Louis Martini cabernet to let it breathe, I placed wine glasses, silverware, and china on my dining room table. Setting a beautiful table would lessen any possible comments about my less-than-stellar cooking skills. I had not been raised in a culinary household. My mother only tolerated cooking; she considered it a daily chore. We had fish on Fridays, salads and casseroles on the other days, and usually went out for dinner on Saturdays. Our breakfasts were orange juice and cereal.

It was late in the day when I started preparing the sauce. I hurried from cabinet to cabinet, whirling around the kitchen trying to get everything ready for my special dinner. It was the first meal I would be cooking for Mike, and I was nervous. While the ground beef browned in a deep, frying pan, I rooted through the refrigerator and found a few onions to chop and threw them into the pan. Mouth-watering smells filled the kitchen. But when I checked the storage cabinet, I saw that I had no tomato paste. As Mike would be arriving shortly, there was no time to drive to town and shop. I improvised with ketchup.

That looks pretty good, I thought as I gazed into the pan. I took a long wooden spoon and stirred the red tomato sauce around the meat and spices.

Then I realized I had forgotten to buy tomatoes. Working at the Times News and owning an international calendar business meant my household chores were often left to the last minute. Or in this case, not at all. Without tomatoes, I improvised again. Outside my back door was an apricot tree. Being about the same color, I thought he wouldn’t notice they weren’t tomatoes. I picked a dozen apricots, washed, peeled, pitted, and cut them into bite-size pieces. Once they were added to the meat mixture, the apricots blended into the sauce. “He’ll never know,” I assumed. But just to be sure, I increased the amount of red wine to my strange concoction.

Hearing Mike pull into my driveway, I added grated Parmesan cheese to a crystal bowl and filled our wine glasses. He parked his pickup and walked to the backdoor, flicking a still-smoldering cigarette to the gravel driveway. Without knocking, he stepped into the kitchen.

“Smells great. What’s for dinner?” Mike asked as he breathed in the onion and garlic and came directly toward me. He wore jeans, his rodeo belt buckle, a snap shirt, and cowboy boots. After a lengthy kiss, I directed him to the dining table and we raised our wine glasses to toast my first-ever dinner, cooked just for him. He sat with his long legs folded beneath his chair and told me about his day at the ranch and his rush to get here from his temporary home in Kimberly. When he started to eat the garlic bread, I understood how hungry he was. I rose from the table and brought in two plates filled with spaghetti and covered with my special sauce.

Mike smiled at me when I placed a dinner plate in front of him. Then he stopped smiling as he looked at the contents. Not sure what to do, he began to push the sauce from one side of the plate to the other. Finally, he bit into the spaghetti.

“What’s this?” he asked as he poked at my imitation tomato.

“What do you mean?” I said as I twirled pasta onto my fork. “It’s my specialty. It’s a spaghetti dinner.”

“What’s in it?” he asked.

As soon as I men

tioned I had replaced the tomatoes with apricots, he started to frown. He picked up another piece of garlic bread and pushed the sauce to the side of his plate.

“I’m sorry, honey, but I can’t eat this,” he said.

Deflated by his comment, I kept my feelings in check and told him we had ice cream for dessert. Knowing about my culinary inadequacy, it’s a wonder he continued to date me. If he hadn’t been so stubborn, he would have realized the special sauce was actually quite good . . . a little tangy but complimented perfectly by the savory, red wine.

Chapter Three

Cattle Ranching

“Want to join me while I check our cattle?” Mike asked a few weeks later.

“Of course,” I said, sliding into the middle of his pickup’s bench seat. Mike swung his right arm around my shoulders, and we began our drive through the foothills of the Albion mountains.

The cattle were located deep in Cassia County and spanned the corners of Idaho, Nevada, and Utah. He went often to oversee the operation, but I only accompanied him a few times. The price of beef had steadily dropped during the previous few years, and the family decided not to continue supporting the losing enterprise. They sold their remaining cattle the following autumn.

As we drove high into the mountains, Mike told me about his family. His relatives had been farmers and ranchers for generations. His parents relocated to Idaho after years of fruit and vegetable farming in Southern California. He was only nineteen when he joined his two older brothers, Gary and Don, at Sky Ranch. Gary, a strong, barrel-chested man in his late forties, was the oldest of the three boys. He moved away from the ranch and bought a machinery franchise in Twin Falls. He had an uncanny ability to fix all things mechanical from antique tractors to WWII airplanes. Don, the middle son, joined Mike and their parents, Margaret and Merle, handling and supervising the ranch responsibilities. Don and his wife, Georgina, and their daughters, Gina Dawn and Sarah, lived in a one-story brick home, a mile east of the parents’ place.

Besides the three Wolverton families, Sky Ranch supported four other men, their wives, and their children. Terry Sherrill was the foreman, a mechanical engineer, and an overall whiz at repairing machinery. Melvin Tipton oversaw the center pivots. Mario Martinez and his cousin, Danny, were their backups. The four men maintained the many irrigating apparatuses, painted machinery, and kept miles of dirt roads relatively smooth and free from snow and floods. Mike and Don joined them during planting and harvesting and hired contract workers to weed and help with extra chores during harvest.

Mike maneuvered one of the ranch’s pale-yellow pickups toward the high pastures. He had tied a red scarf around his neck and wore an off-white cowboy hat. We passed several gates on our way up the mountains. Mike stepped out to open and shut them while I slid to the driver’s seat and drove the pickup through the wide opening. Soon we came to a cattle guard. I had never seen one and realized the object worked just like a fence. A vehicle could drive over the guard, saving the need for Mike to get out and unfasten a gate. The rancher had a depression dug in the dirt between two fence lines. Next a dozen metal bars or tubes were laid inside the recess, perpendicular to the road. He placed them about six inches apart and painted them bright yellow or orange. If an animal tried to cross the barrier, its feet became stuck in the contraption. On the whole, the cattle knew not to attempt a crossing. It worked just as well as a gate, keeping stock wandering from field to field.

At one span we came upon a Hereford bull whose foot had lodged between the metal tubes. The brown and white bovine bellowed in distress. Slobbery grass hung from his mouth as he tugged his wedged foot. There was no way Mike could get him out by himself, and his handheld Motorola radio did not work that far from the ranch. We crossed the cattle guard just inches from the angry bull.

“One of the cowboys will be checking the pasture today,” he said. “He’ll figure out what to do.” And he was right. When we returned a few hours later, the bull was gone.

The trail narrowed and shrubs brushed against the sides of the truck. At a watering trough, high in the sage-scented mountains, a group of cattle had gathered. Most were black Angus, a breed derived from Scotland, but a couple were creamy white. The Charolais, a breed originating in France, mingled with the herd. As we sat in his truck surveying the cattle, Mike told me when Charolais are bred with Angus, the offspring are not as feisty and are easier to handle.

“Angus mothers are tough protectors,” he said.

“What’d you mean?”

“I had one jump into the back of a pickup when we were doctoring her calf. Talk about panic time! When she jumped in, we instantly flew over the side rails. No way were we getting in her way!”

“What do you mean by doctoring?” I asked, smiling as I imagined the mother cow and two or three cowboys jumping in and out of the back of a pickup.

“Sometimes we’d rope a calf. And sometimes we’d put it in a squeeze chute. And if there’s one small calf, we’d pick it up and swing it into the back of a truck.”

“Then what?” I asked, so curious about all I saw. His was a lifestyle I knew nothing about, and I was interested in Mike’s answers.

“We’d take its temperature and give it a round of vaccinations.”

“What about the ear tags?” I asked, pointing to the plastic, yellow tags hanging from each cow’s ear.

“That’s a recording device. We use the tags instead of branding. See the number on each tag?” he asked.

“The one closest to us is Number 116,” I replied.

“That’s an identification number. It tells the animal’s history, its lineage, past owners, and latest inoculations. It can also help track contagious diseases,” he explained.

“Sometimes we’d accidently round up another rancher’s cow,” he continued. “With the number, we can get it back to its rightful owner.”

Mike went on to say, “Besides doctoring the calf and attaching ear tags, we’d dehorn and castrate him.”

“Wow! No wonder the animals run from cowboys,” I said as I surveyed the herd, nodding my head as I heard his answers. “So, tell me, what’s a squeeze chute?”

“Am I your own personal cowboy encyclopedia?” he teased before he continued to answer my questions. “See that green metal object to the right? It’s a portable chute. We trailered it here a few weeks ago.”

“Yeah. Then what?”

“It’s adjustable and can control the calf by squeezing its sides. And it locks the head still. With the calf inside, we can do everything without hurting ourselves or having the calf break loose,” he added.

“How do you castrate a bull?” I asked.

“A cowboy slices between the balls and uses a clamp to actually remove the testacles. He then places a special bandage over the gap. It not only closes the opening but also medicates the site.”

“Gad, that makes me sick,” I said.

“Not as sick as the bull feels,” Mike laughed. “Haven’t you heard of ‘Rocky Mountain Oysters’? That’s something Don likes.”

“Oh, no. He doesn’t eat them, does he?”

“Yup. He and some friends have a few drinks, roll them in flour, and deep fry them. He says they’re pretty good.”

“I’d need more than a few drinks to try that,” I countered. “Nope,” I amended my thought. “I couldn’t even do it with liquor.”

Confined in the Ford truck for a few hours gave us plenty of time to share life stories. I knew he had two children from a previous marriage and that they lived with his former wife. I told him of my previous ten-year marriage and numerous funny stories of fishing around the world.

Further down from the mountain as we bumped along the dirt and gravel road, Mike told me about the time a few years earlier when he and Lou, a hired cowboy, had trucked their horses to handle some doctoring high in the mountains. They wore leather chaps over their jeans and cotton bandanas around their necks. The chaps protected their legs from thorn and mesquite bushes. They used the bandanas to wipe swe

at from their hands and faces and to cover their mouths and noses if an unexpected dust storm materialized. Surprisingly, they didn’t use them to blow their noses. Instead, they would close one nostril and blow hard, aiming the nasal material into nearby bushes. For me, that’s when the romantic image of a cowboy crossed the line. My father would have been disgusted by the practice. He always used a monogramed, Brooks Brothers handkerchief to blow his nose. Nothing less would do.

Mike continued to reminisce about his life. One time he and Lou trailered their horses but didn’t bring a squeeze chute as there were only a few calves to catch. Throughout the day, Lou continued to rope calves’ heads while Mike roped their hind feet. After each man had connected to the calf, they looped their rope several times around the saddle horn. As I learned, the men would “dally” or wrap the rope. Then their horses would back up, stretching the calf. This ensured a solid anchor as the calf had to pull against both the horse and rider.

“I’d jump off Shamrock and race to the calf, push it on its side, and wrap a short rope around its legs,” he said. Once the calf was secured, they’d proceed with doctoring.

Mike told me about riding Shamrock, his quarter horse, one particular day with his border collie stalking the strays. All day long, Lou and Mike and their horses roped and worked the calves like well-oiled machines. It was toward dusk when the unexpected happened.

Lou lassoed the last calf around its head, and it stormed out in the opposite direction. Mike kicked Shamrock and off they charged to rope the calf’s legs. Just then he heard a shriek. Mike turned back to see Lou holding up his hand. His index finger was missing.

“What happened?”

“My finger got caught in the dally. When the damn calf bolted, the rope burned off my finger.”

“Christ! Get off your horse. I’ll trailer them back,” Mike exclaimed. “You get to the hospital.”

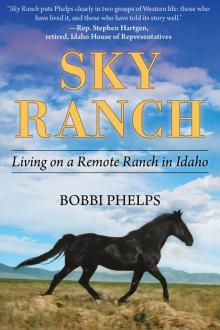

Sky Ranch

Sky Ranch